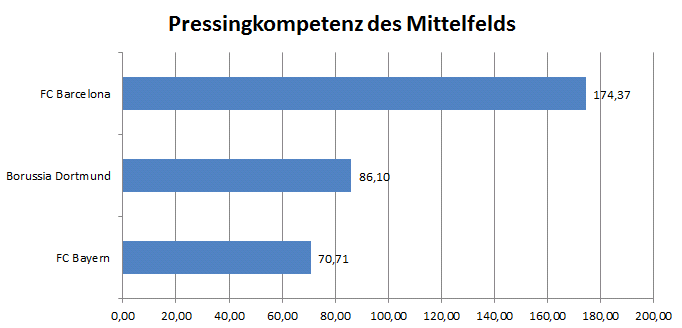

14 out of 19 trophies were won in his time at FC Barcelona. 4 trophies out of a possible 6 were won in his first season with Bayern Munich. This piece will analyze the Juego de Posicion football philosophy of Pep Guardiola in his second season with Bayern Munich. The Italians know it as “Giochi di Posizione[1]” and the Dutch call it “Positiespel.” In English we will call this philosophy of football “Positional Play.” Viewing football through the prism of Positional Play is perhaps the main reason for the success of one of the greatest football coaches in history.

*Note: I expanded upon the philosophy of Positional Play in an interview with LeftWingSoccer. The interview is a follow up to this piece which includes questions about Positional Play coaching, tactics, strategy, and more! You can find the interview here.

The Principles of Positional Play

Positional Play is a philosophy that has many principles but the fundamental principle is the search for superiority. There are various ways to gain superiority and various types of superiority that can be achieved. Once superiority is found the team can use the situation to dominate the game. All other principles stem from this idea as mentioned in this extract from an exclusive interview I had with Marti Perarnau[2]:

“Positional Play does not consist of passing the ball horizontally, but something much more difficult: it consists of generating superiorities behind each line of pressure. It can be done more or less quickly, more or less vertically, more or less grouped, but the only thing that should be maintained at all times is the pursuit of superiority. Or to put it another way: create free men between the lines.

Positional Play is a model of constructed play, it is premeditated, thought about, studied and worked out in detail. The interpreters of this form of play know the various possibilities that can occur during the game and also what their roles should be at all times. Naturally, there are better and worse interpretations. There are also players that never manage to adapt to this model of play, which however, are sensational players and they manage to contribute many virtues to their team.

But in general, the interpreters of this model need to know the catalog of movements that need to be executed in depth. As in any piece of music, one same score gives rise to many different interpretations: faster, slower, more harmonious… more or less a concrete interpretation that you like, but what should be kept in any case is that the tune is similar to the original. Positional Play is a musical score played by each team who practice it at their own pace, but it is essential to generate superiorities behind each line of the opponent pressure. The team that interpreted Positional Play in a most extraordinary way was the Barcelona of Pep Guardiola.

When the coach left, the team continued playing the same game,but they were gradually losing focus and intensity in fundamental movements to the point that it became a very flat and predictable variation of play with a tendency to pass horizontally that ultimately reduces the possibilities of generating superiorities after lines of pressure of the opponent. This was one of the main problems Barca suffered in the last two seasons, although it was not the only one.

In Bayern Munich, Guardiola has promoted the Positional Play that Louis van Gaal introduced five years ago. But the one Bayern is practicing right now is a game that is much more oriented to a vertical axis than a horizontal one and this version requires a high degree of technical excellence because it seeks to construct the above mentioned superiorities not based on horizontal but vertical passes. This is an extremely ambitious interpretation of Positional Play.”

– Marti Perarnau

Superiority in positioning is necessary to be able to penetrate the opponent’s defensive lines, move the ball efficiently, and to have stability in possession. One form of superiority is numerical superiority. Having a numbers advantage means that your team has a free man. The goal is to find the free or unmarked man by moving the ball, positioning, or player movement. The free man in your attack has the best situation on the field and is very valuable to the attack. This is exemplified in this quote by Juan Manuel Lillo[3]:

“Look for the 3rd man (free man) to be able to turn and face the play.”

– Juan Manuel Lillo

For example, when trying to escape pressure it is recommended your team looks to play a long flat pass to the 3rd man. This is a key principle in avoiding counter attacks. The 3rd player provides an option for a long pass and as a result as they usually have more space and a more efficient view of the field. It is common to see the top teams execute a layoff pass after playing a long escape pass.

A long pass generates pressure at its destination as it gives the defense more time to read its flight as well as more time to arrive. So, once a long pass escapes pressure and the pressure gathers near the destination of the pass the ball is laid off to another teammate. This allows the ball to be given to a player who now has a better view of the field and much less pressure around him than the player who played the layoff pass.

The free man must always be supported in order to take advantage of their value. To provide this support, Guardiola’s teams usually underload the farthest point away from the ball, i.e. they leave the furthest diagonal point roughly unoccupied while the team supports areas around the ball aggressively.

These underloaded areas are the least important for the immediate play, though they also play a role. Guardiola’s teams seek to have superiority in the center of the field. Permanently occupying the center means that players always have an option to pass to. The manner in which Guardiola’s players support each other means that the player will always have at least 2, and preferably 3, passing options.

This of course forms triangles and diamonds in the playing structure. An infamous example of Pep abandoning this principle is the 0-4 loss to Real Madrid in the Allianz Arena. His Bayern team played in a 4-2-4 formation which meant that the central areas were not controlled and the players in the center were not supported. This area of isolation caused Bayern to lose the ball in dangerous areas and have difficulty generating dangerous attacks.

A classic example in the search for numerical superiority in Positional Play is called “Salida Lavolpiana,” or “The way out of La Volpe[4].” This is a variation of progressing the ball out of the back in possession. Many times Pep will have players drop into the defensive line if the opponents pressure with the same number of attackers as Pep’s defenders. The value of this idea is mentioned here by Lillo:

“Positional Play consists of generating superiorities out of the defensive line against those who are pressing you. Everything is much easier when the first progression of the ball is clean.”

– Juan Manuel Lillo

Using the goalkeeper is also another way to establish superiority out of defense, progress past the opposition lines and move up the field to create an advantageous attack. Salida Lavolpiana is a variation in which the central defenders fan out wide and a central midfielder drops into the resulting space. This briefly creates a back 3 in addition to having the goalkeeper as a base for the progression of the ball.

This is used most often when an opponent pressures 2 central defenders with 2 strikers. This movement creates a 3 vs. 2 situation out of defense, meaning a free man is available. The fullbacks push up into midfield as the central defenders fan out not only to provide a pass option, but in order to provide numerical superiority in midfield as well. This ascending superiority provides an advantageous path towards the opponent goal. Juan Manuel Lillo mentions this as one of the principles of this style of play:

“Pass to the next lines of play.”

– Juan Manuel Lillo

Pep Guardiola uses these principles of play himself, as everyone has become accustomed to seeing the wide central defenders and the midfielders dropping into the defensive line. Marti Perarnau talked about the origin of Salida Lavolpiana here:

“Although in Spain it became common in the 2009-2010 season of Josep Guardiola with FC Barcelona, it is in Mexico where this concept is used most. La Volpe practiced this with his teams since the mid90s, including the Mexican National Team during the time when Guardiola played for Dorados de Sinaloa, during a time when the Catalan coach could approach La Volpismo .”

– Marti Perarnau

Another form of superiority is one of qualitative superiority. This is an idea that is well known. Searching for 1 vs. 1’s, 2 vs. 2’s, and more with your best players vs the opponent’s worst players is a common strategy in football. This is perfectly exemplified in this quote by Paco Seirul-Lo[5]:

“There’s numerical, positional, and qualitative superiority. Not all 1 vs. 1’s are a situation of equality”

– Paco Seirul-Lo

As mentioned in the above quote by Paco there is another form of superiority besides the 2 already mentioned. This is a superiority of space or positional superiority. In this form of play the players are arranged at various heights and depths. This staggering creates interior spaces and passing lanes within the opposition’s formation. There is a large focus on the spaces “in between the lines.” Players look to position themselves in areas between the opponent’s horizontal and vertical lines of defense.

There are specific zones that must be occupied by players in specific moments. The specific zones or positions that must be occupied depend on various circumstances. A certain set of players within the team occupy the specific zones in relation to the ball, though the players who do this can vary because of the flexible interchanging of roles. A player determines where they will move by referencing the position of the ball, their teammates, the opponents, and space. Arrigo Sacchi[6] made a similar point when speaking about the defending of his great AC Milan team:

“Our players had four reference points: the ball, the space, the opponent, and their own teammates. Every movement had to happen in relation to these reference points. Each player had to decide which of these reference points should determine his movements.”

– Arrigo Sacchi

These superiorities or overloads provide interesting effects in the game. Combinations become tighter and quicker when a space is overloaded. It’s possible to break through the defense on the near side of the field, to open spaces on the far side of the field, and it allows for the stable possession.

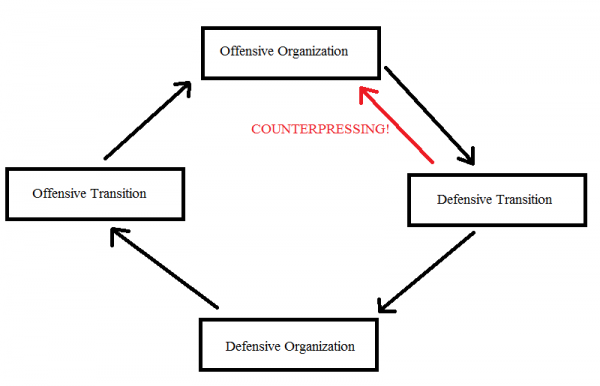

The staggering of your team’s positioning in possession directly translates into better structure when counterpressing after the ball is lost. Counterpressing refers to pressing the ball immediately after possession is lost; a well known factor of Pep Guardiola’s teams. The offensive and defensive aspects of the game cannot be separated in Positional Play.

The team’s offensive ideas have a direct impact on their defensive work. Therefore, the team’s ideas in possession set the tone for all other aspects of the match. Guardiola even has a “15-pass rule,” in which he believes that his team cannot be properly prepared to cope with transitions or build a well structured attack until they have completed at least 15 passes. This provides enough time and stability for players to move into their roles within the offensive structure and strategy. Johan Cruyff[7] talked about the success of Barcelona in defensive transition due to their aggressive ball-oriented support while in possession here:

“Do you know how Barcelona win the ball back so quickly? It’s because they don’t have to run back more than 10 metres as they never pass the ball more than 10 metres.”

– Johan Cruyff

Oscar Moreno[8] elaborates on the importance of controlling all phases of the game simultaneously here:

“Provoke the proximity of the maximum number of opposition players around the ball. Recuperate the ball imminently when lost in spaces where we are united. Divide the play of rival team while not dissociating ours. All with the idea of having awareness of, during the prices of attacking, I am generating the futures conditions defensively or vise versa.”

– Oscar Moreno

This relates both to defensive stability coming from offensive stability, and another aspect of the way Guardiola sees football. For Pep, this also applies to the idea that general concepts within the phases shouldn’t be separated. Some concepts which are used exclusively for defense can also be used for offense.

For example, in football the defense are the ones that are proactive, meaning that they determine how the game will be played due to them defending their zones in order to block access to the goal. The defense makes the rules, the offense reacts to the defense and try to score goals to win. Pep tries to change the state of modern football, while other managers attempt to win the game.

His offense attempts to be the proactive one, to determine how the game of football will be played, to take away the control of the game from the defense. Meaning the offense determine how the defense will react instead of the defense determining how the offense will play with the ball. He uses the ball to manipulate the defense. This is a key shift in the balance for control in a football match.

To add onto this idea, through hard training his players are able to work well with each other to control phases of the game where nobody seems to be in any real control. For example, when Pep’s teams lose the ball they counterpress immediately, as mentioned above. This means that even in transition phases they seek to act rather than to react to the change in play and rhythm.

They press immediately and determine what the opponent will do in the moment of transition, rather than dropping off and allowing the opponent to decide how they will transition. They cope with all conditions of the game better than the opponents do. The conditions for all of these concepts to come into play are constantly being generated, even while in possession and creating the offensive structure.

Within the structures created in possession, a main principle of supporting the ball is creating triangles or preferably diamonds. Formations are not entirely important to Pep Guardiola. They are merely numbers. He cares more about the perfect coverage of the field in relation to the ball.

Forming triangles allows players to have better orientation on the field and creates uniformity in movement. Depending on the ball’s position the players will position themselves in a way that allows them to move it into important areas of the pitch. If the ball is on the left flank in attack, the positions that must be occupied are completely different than the positions that must be occupied if the ball is in front of your own penalty box.

Players can perform specific movements while in these positions in relation to each other. These include but are not limited to: overlapping runs, diagonal inside runs, and providing a back pass option. There are general “rules” within these methods of structuring the player’s positioning in relation to the ball. These do not have to be followed strictly but are recommended to provide continuity and flow to the game. The idea is that a maximum of 3 players may occupy a horizontal line on the field at one time, while a maximum of 2 players may occupy a vertical line at one time.

If a system has natural triangles in its design than it is that much easier for the players to form triangles in possession. This is one of the many reasons we see formations with variations like 4-3-3 or 3-4-3 being used in teams who play this way. Every player is connected to one another and they move like chains throughout the field in order to have the best structure in possession and support their teammates and the ball. Oscar Moreno mentions the interconnectedness of all the players on the field here:

“Every action implies the subsequent action for receiving the ball.”

– Oscar Cano

Another key principle of Position Play is the manipulation of the opponent.

“The objective is to move the opponent, not the ball.”

– Pep Guardiola

Every single action that happens on the field must have a purpose. The ball doesn’t move just to move. The ball is moved in order to move the opponent, to gather them on one side while you plan to attack the other. Every pass has the intention of building up to the action of eliminating opponents. If it isn’t possible to eliminate opponents then the players will keep the ball and look to get the opponents to move out of position. The ability to do any of these actions is supported by the structure in possession talked about earlier.

The free man is an extremely important character in terms of manipulating the opponent. This is achieved mainly through switching the ball to the opposite site of the field once the opponents have gathered on one side. Usually the free man is the unmarked player on the opposite side of the field and he has the best value to the attack. The ball is a tool that is used to eliminate opponents and manipulate their defensive balance. The ball isn’t held in possession just for the sake of having the ball; possession is a consequence of this style of play.

Teams that use this philosophy of Positional Play determine which spaces they want to attack based on the game strategy then use a distraction in another area before striking the opponent in the desired area, i.e. playing on the left side to gather the opponents there, in order to finish the attack on the right or playing in deep areas to lure the opponents out in order to finish the attack in behind the opponent in the open spaces. We see that specific mentality of play even in counterattacking teams. Juan Manuel Lillo summarizes this concept here:

“The principle idea of Positional Play is that players pass the ball to each other in close spaces to be able to pass to a wide open man.”

– Juan Manuel Lillo

We have looked at the principles of Positional Play and strategical examples of the principles, but it is also important to look at how this philosophy relates to the specific movements and ideas of its players. The ball can move via dribbling, passing, or shooting. A player must master when and how to do any of these movements in order to create an advantageous situation for the team.

Each movement can cause the opponents to concentrate their positioning more towards the ball which opens other spaces on the field. Lionel Messi and especially Andres Iniesta are masters of this. They create spaces by drawing many players towards them. It can be considered a sort of “offensive pressing trap,” because they invite pressure from many players then escape it and conquer the resulting spaces with their teammates. Johan Cruyff talked about the types of players he wants specifically:

“I want players who can make decisive moves in small spaces, I want them to work as little as possible to save energy for that decisive action.”

– Johan Cruyff

In general, players should always choose passes that provide continuity to the game and they should always look to secure the passes by supporting them. For example, if the opponent is compact the orientation of the game should be changed with longer passes. If the opponent is not compact then it is better to combine in short movements to exploit these spaces quickly.

Both types of passes should be used flexibly though. The players will look to move the ball as quickly as possible so that the opponent cannot react in time and so that the forwards have the edge in game rhythm. In terms of positioning, standing between the lines attracts the attention of more than just one player, which can be beneficial to others.

The men between the lines, called interiores, dominate Positional Play. They are in between their opponents and this separation from their opponents is precisely what causes the gathering of opponents in specific areas. They are masters at eliminating their opponents and avoiding movements that attract opponents to an area where the opponents have defensive access to the ball. The players positioned in between the opponent’s lines should constantly move in order to have an open passing lane between them and the ball, or between them and a player who has an open passing lane in relation to the ball.

Staying out of the cover shadow of the opponents means that the opponents cannot block you with their positioning and invites more than one opponent to worry about this player. The specific manner in which a player receives the ball could also affect how they are marked.

Movement of the ball and the players is how signals are communicated in football, so if a player checks into a space to receive a ball very quickly, the defenders might match this intensity and follow the player and leave a free space to be exploited, or a free man. Siegbert Tarrasch[9] talks about chess in a way that is comparable to this aspect of Positional Play:

“Weak points or holes in the opponent’s position must be occupied by pieces, not pawns.”

– Siegbert Tarrasch

Meaning that your very best players should be the ones who are the men in between the lines. They are the ones who will most skillfully exploit the holes in the opponent’s defense as well as perform the most valuable actions for the team. Examples of these players in Guardiola’s time with FC Barcelona are: Xavi Hernandez, Lionel Messi, Andres Iniesta, and Sergio Busquets.

The fullbacks or wingers are usually very wide and open on the sidelines of the pitch. They stretch the defense and create interior spaces and passing lanes. The opening of these spaces provides a better environment for the interiores and creates superiorities and free men in the most strategically important area of the field the center.

The defenders build the game from defense and should determine the beginning of the attack. If the opponent is sitting deep and the strikers aren’t pressuring it is the job of the defenders to move towards the opponent and attack them in order to disorganize them. These are all main principles that Guardiola uses with his teams when teaching Positional Play.

*Note: Here is a video made by Felipe Araya and FootballHunting of Pablo Adrian Guede’s CD Palestino, a first division Chilean side. Guede is an Argentinean coach who in his playing days was a striker for various clubs, such as: Nueva Chicago, Deportivo Espanol, Xerez CD, Malaga, and Elche. In his time in Elche he befriended the former FC Barcelona head coach (and assistant coach to Pep Guardiola) Tito Vilanova. He has coached CD El Palo, Nueva Chicago, and just recently took over the job as manager of CD Palestino from former coach Emiliano Astorga. Guede introduced the Juego de Posicion philosophy of football and has taken CD Palestino to their first Copa Libertadores in 35 years.

http://vimeo.com/115136383

Pep Guardiola

Pep Guardiola’s first season with FC Barcelona’s first team was during the 2008/2009 season. In 2007 he was a writer for El Pais. Even at that time it was easy to see his philosophy of football shine through his writing. At a time when Frank Rijkaard[10] surprisingly used a 3-4-3 against Zaragoza in the 2007 season, Pep Guardiola had this to say in his article:

“I think, and maybe I’m wrong, but what I see is: [Barcelona] like to organize themselves according to the ball—that they attack and defend with the ball and understand that it is unacceptable that the ball is there and we are here. The players feel that, instead of moving towards the ball, the ball will reach them where they are. They feel that, in order for the attackers to succeed and appear in the newspapers, [they] need a good ball from the midfield and they, to do so, need a good ball from their defenders. I will pass it on to you and you pass it to them.

Ronaldinho knows that he is better with Eto’o and Eto’o knows he is better with Ronaldinho. They have their aspects, but are better together than alone. They insist on knowing where the free man is at every moment, and know that it is better if that man is Iniesta rather than a winger. They know that Xavi and Iniesta are compatible. And why wouldn’t they be, dammit? They understand, as all good collectives should, that when you start on the right, it is better to finish on the left end and a back pass does not indicate fear, but the beginning of another, better play.

They feel that the time will come and that possession itself is nothing, but rather a means to reach the goal. That it is better that the ball reach the extreme end of the pitch via the center rather than from up the sides. And with all this, sometimes, occasionally, they also lose. They lose through lack of will power, by not getting their shirt sweaty enough. Or because they have recently eaten too much and too well, and they have lost their appetite.

Yes, they also lose for these reasons, like all teams around the world. But they also lose because sometimes, Xavi or Iniesta or Deco will steal the ball from the midfielders when perhaps they should not. Or because the ball that starts on the right is on track to finish on the right. Or because the third man is seldom used. Or because Ronaldinho has to receive more passes from Marquez and fewer from Sylvinho…Or because the attack-defense transition, to have it or not have it, was seen and unseen, and now maybe the best is slower.”

– Pep Guardiola

This extract perfectly exemplifies the views and passion of Pep Guardiola. This is what makes him one of the best ever. In regards to Positional Play, Pep said only 3 teams in the world truly play this way. Swansea City under Laudrup, Rayo Vallecano under Jemez, and his Bayern Munich. This alone shows that there can be some problems with the complexity of this concept. It may be difficult to implement in training and for the players to grasp. Each coach has their own variation of Positional Play that fits their team and their personal philosophy.

Guardiola’s teams play defense very aggressively. The main focus is on zonal marking instead of man marking. Zonal marking gives the initiative to the defense and they determine the offense of the opponents, while man marking is a reactionary defense at best. In man marking players must react to whatever the opponent does, meaning a loss of control. While in zonal marking the defending team determines where and how they will defend and the opponent must play against them to control the game. There is a focus on the passing lanes between the opponents.

The opponents all seem open to the ball carrier but the defenders are closing the passing lanes while all pressuring the ball together. Guardiola’s teams counterpress. The moment the ball is lost is the perfect time to press the opposition because the opponent is disorganized, especially the player who won the ball.

The player who won the ball usually loses his awareness of how the game and the field positions have changed when he wins the ball. So the player who lost the ball leads the hunt and Barcelona press the ball in a “wolf pack,” blocking the passing lanes to the opponent’s teammates while closing down the player on the ball very quickly before he is allowed to escape or the opponents regain stability.

“Move the opponent, not the ball. Invite the opponent to press. You have the ball on one side, to finish on the other.”

– Pep Guardiola

Guardiola’s recent teams have been the best in the world and they follow these principles. They have purpose in every pass and look to take opponents out of the game very frequently. Many times you will be able to see players not passing the ball until receiving some sort of pressure. Boateng and Dante will sometimes stand completely still with the ball until a player presses and then they pass the ball away.

This shows the complete dedication to manipulating the opponent’s movements with the ball. Sometimes Iniesta will be in the middle of the field and he will just stop doing anything. This famous move is called “La Pausa” or “The Pause,” He stands completely still while opponents begins to pressure him and abandon their defensive positioning, creating holes in the defense and free men for Iniesta’s team.

Another interesting aspect of Guardiola’s teams was the use of a “False 9,” a player who is the center forward, but does not occupy the center forward position at all. An interesting quote by Guardiola perfectly summarizes his views on this style of play:

“Everyone is allowed to move into the box, but none are allowed to stand in it.”

– Pep Guardiola

Meaning he expects every single player to contribute to the support of the ball and the build up play before entering the penalty box to finish the move off. This means his strikers don’t usually just stand up front and wait for the ball, but are actively and fluidly involved in the build up play, while even the midfielders and defenders can finish the move in the box if the situation allows them too.

This provides interconnectedness within the team as well as confusing the opponent. When Messi was introduced as the False 9 vs Real Madrid in the Santiago Bernabeu for the first time, Madrid’s central defenders admitted they had no idea how to defend Barcelona, and they lost 6-2 on the day.

In regards to superiority in possession, this quote by Angel Iturriaga[11] perfectly captures the talent of Mr. Guardiola:

“Guardiola has sublimed Positional Play. He introduced variants in taking the ball out [of defense] that didn’t even cross La Volpe’s mind. He is an innovator and an excellent scholar. I think it is impossible to repeat that virtuoso cycle. As a coach, I would say his capacity to manage a group and egos stands out, his capacity to work and his capacity to change matches tactically. He is able to use 4 guidelines in a match and change them depending on how the rival is situated.”

– Angel Iturriaga

The variants Iturriaga speaks of are actions such as: the defensive or central midfielder dropping towards the sides of the central defenders, defensive or central midfielders dropping into the spaces in between a formation with 3 central defenders, the fullbacks pushing high and inside towards the center, and more. These variants allow for interesting changes in build-up play. Like Lahm being able to receive towards the sides instead of in the center and progressing diagonally towards the opponent goal.

Continuing with the idea of progressing the ball out of the defense, this quote by Guardiola shows his style of thinking and strategy when facing opponents:

“In football each player is responsible for another except in the [2 central defenders] vs. [1 striker] tip of each team. We start our 2 vs. 1 with a central defender driving out towards the opponent goal, causing an opponent out to prevent his progression, freeing his [partnering central defender] (generation of free man). Danger! If we lose the ball the opponent strikers have a 1 vs. 1 against our defenders. Each team decides how they will play now.”

– Pep Guardiola

Guardiola is willing to take the risks necessary to be successful. It may not look like a dangerous situation, but it takes real bravery to leave your team matched up man for man against the opponent forwards while your team is in possession trying to create a chance and the defending team is sitting back waiting to counter. It takes bravery to split your central defenders extremely far apart from each other to the touchlines of the pitch while under pressure. All of this is done in order to constantly adhere to the principles of Positional Play, no matter the cost.

Guardiola chooses different players in his starting lineups based upon how he interprets their movements and their synergies between other teammates on the field. He plans specific movements in regards to the opponent and what the strategy on the day calls for.

His tactical moves always fit the team and he doesn’t change the team in order to fit his tactics – or else they will play very badly. In terms of being a manager, Guardiola has his philosophy, is great at creating strategies against his opponents, excellent at the specific tactical movements required to execute the goals of the strategy, and is also world class when it comes to in-game changes.

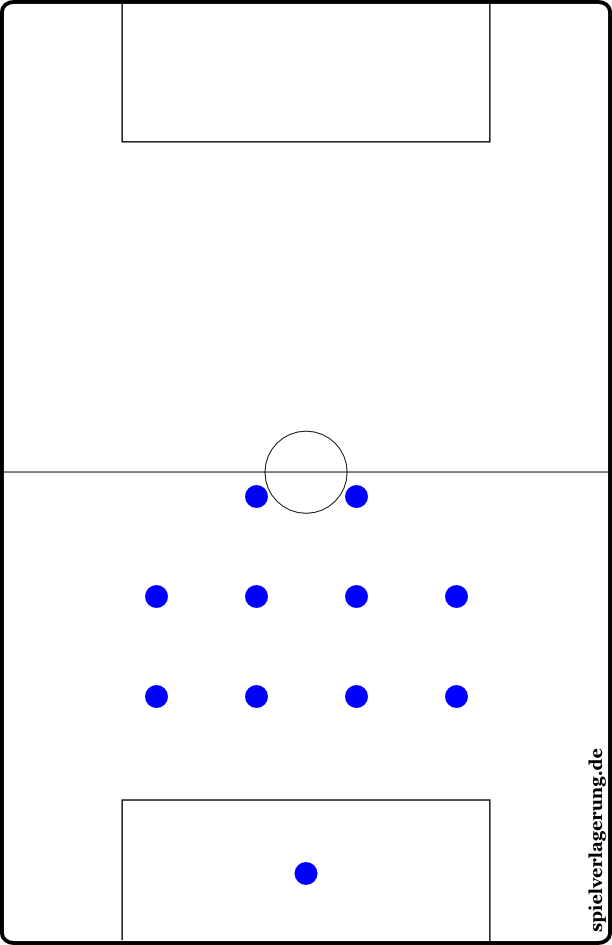

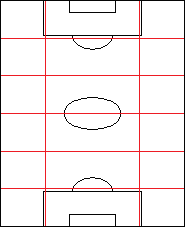

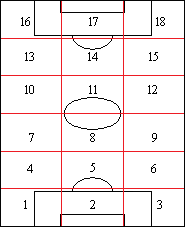

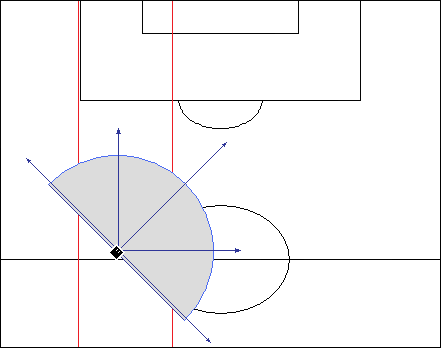

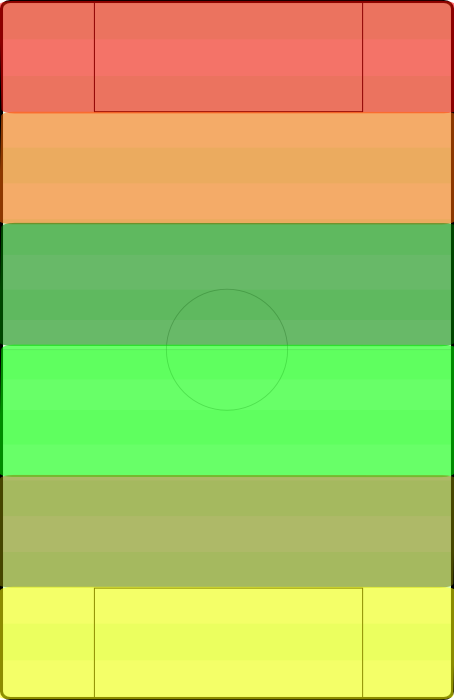

When it comes to training this philosophy, Guardiola has a specific training pitch in which he trains his players:

![Pep Guardiola's Training Field.]()

Pep Guardiola’s Training Field.

He trains his players on this pitch and trains them to orient to these specific lines on the field.

“The only important things in our game are what happens within these 4 lines. Everything else is secondary.”

– Pep Guardiola

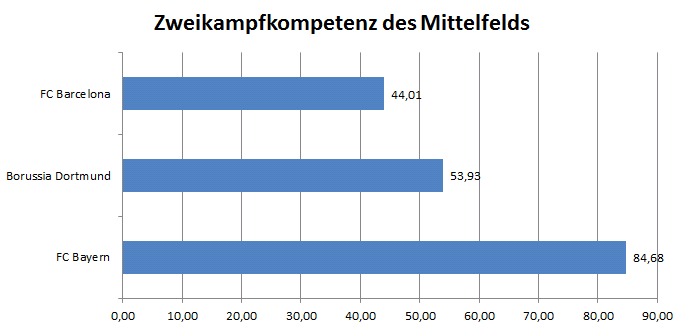

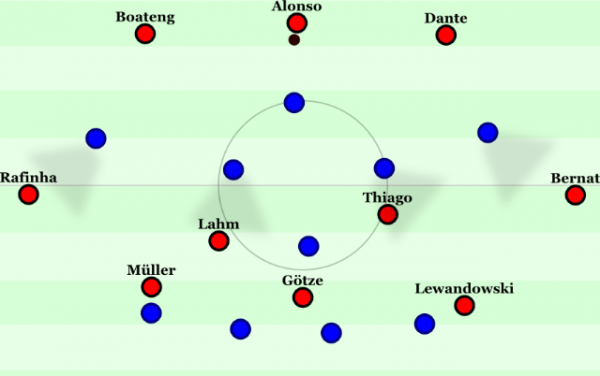

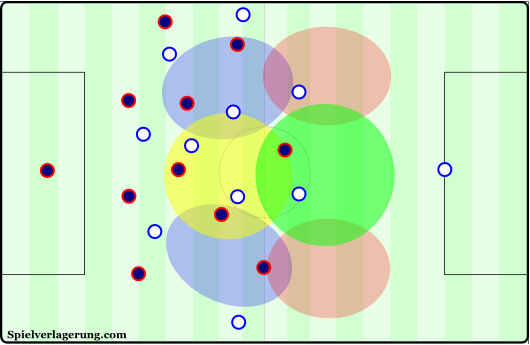

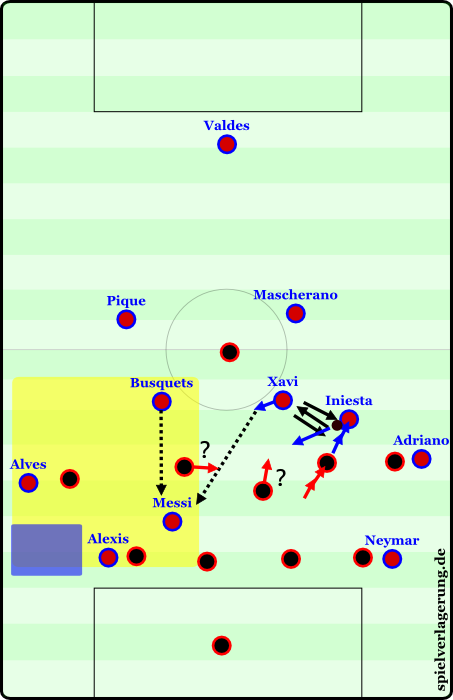

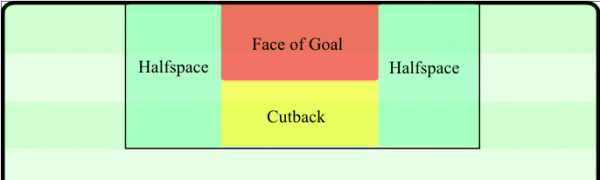

The four central lines are of utmost importance. This is where the men in between the lines play and it is the most important portion of the field for Guardiola. There are 4 vertical lines and 5 vertical strips of space on the field. The flanks are the outside vertical strips, the 2 inside strips are called “interior corridors[12]” in Positional Play, and the central strip is the center.

The interior corridors are arguably the most important spaces within the center, as this is usually in between all lines of the opponent defense. From here, players can have the biggest impact in eliminating opponents as well as moving diagonally towards the goal, which has its own specific benefits that will be mentioned in the game analyses.

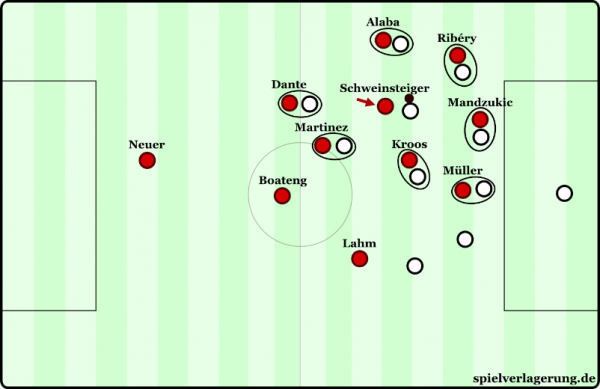

On this field, Pep trains his players how and where to move in relation to the ball. If the ball is on the left flank and Ribery has the ball, there are various movements that can be trained to support Ribery while maintaining great positional structure and stability. For example, Ribery can begin dribbling inside, and Alaba the left back will move from the interior line to occupy the left flank that Ribery is exiting, with a possibility for an overlapping run.

Meanwhile, the near side supporting central midfielder like Schweinsteiger would move deeper and toward the left outermost vertical line of the 4 central vertical lines. This means that Ribery is dribbling inside towards goal, Alaba is giving him an overlapping run option, and Schweinsteiger is moving deeper and in between the two – forming the tip of the triangle while the other two attack.

At the same time, the rest of the team is reacting to these movements in order to have the most efficient positional structure and stability in play. During the training of these movements the general rules of never having more than 3 players on a horizontal line at the same times and never more than 2 on the same vertical line at the same time is being obeyed and thought about constantly by the players. So even the far side players are chain-reacting to these movements and forming the optimal far side structure to be able to attack if the ball is switched across to the center or the opposite flank.

This is just one example of a specific movement that could be trained using this field. Guardiola can add defenders and train specific situations and eventually the players can play on any field without a need for guidelines to help orient themselves. The players over time learn all the variations and principles that come with training on this field and use it flexibly and interchangeably. Eventually the players move extremely fluidly and all have the same mindset and sense of orientation on the field.

*Note: Here is a famous video posted by tz.de on YouTube of Guardiola training his Bayern Munich team in the art of Positional Play during the winter break of his first season with the team. He talks about the length and angling of the central midfielders in relation to each other in order to have optimal positioning to penetrate the defensive lines, specific runs/movements the players should be doing, decision making with the ball to manipulate the opponent or maintain stability, and more.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6YDl1dFI5g

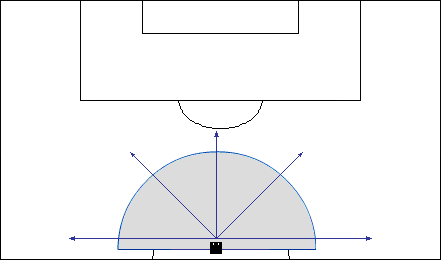

Along with that form of training, Guardiola also plays various other games that improve the fundamentals needed when it comes to Positional Play, e.g. game intelligence, movement, body angle and position, clean passing technique and dribbling, awareness, and more. Another example of a game that is used in training constantly is the very famous Rondo:

![An 8 vs. 2 Rondo.]()

An 8 vs. 2 Rondo.

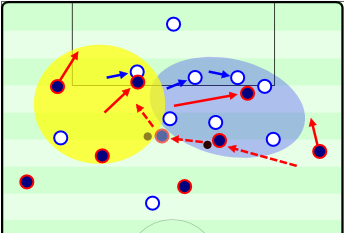

The most common Rondo seen in Guardiola’s training sessions is in a 10x10m square in an 8 vs. 2 “Monkeys in the Middle” game dynamic. Usually it is played with one touch passing, but that can be changed depending on the parameters. The size of the square as well as the amount of players on each team are variable as well. This is an example of the most basic Rondo Pep uses.

The goal is usually to reach 20 or 30 passes in a row without an interception. Once that is achieved the players all tease and applaud towards the players in the middle. If you watch any of the recent training videos uploaded by Bayern Munich on YouTube you can hear players like Mueller counting each pass out loud.

The focus of the training can be either the defenders (Monkey in the Middle) or the attackers (Circle). Usually the defenders can switch out with an attacker only when they intercept the ball, not when they poke it away – promoting intelligent positioning. Once this happens, the attacker who lost the ball then joins the defender in the middle while the defender who intercepted it joins the circle.

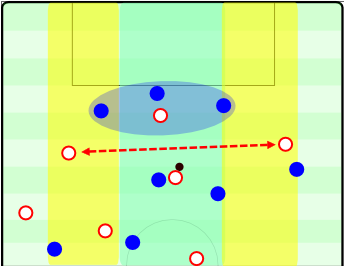

In a Rondo, there are specific passes like a 1st line pass, a 2nd line pass, and a 3rd line pass. A 1st line pass doesn’t bypass any defenders. A 2nd line pass bypasses a defender but doesn’t split the two defenders in the middle. A 3rd line pass is the ultimate goal and is a pass which goes between the two defenders in the middle. The players on the outside may move around and change their body position at any time.

The goal is to manipulate the defenders in such a way that you can play a penetrating pass in between them. During the exercise the intensity and speed of the ball is extremely fast and requires great technique and concentration. The players constantly adjust the angle of their positioning in relation to their teammates, sometimes taking a step backwards or forward on the edges of the square, sometimes turning their hips in a certain way so that they can play the next pass or receive a pass efficiently. They can also move closer to their teammates in order to invite pressure before playing a longer pass out of pressure to continue the passing streak.

There are various fundamentals that are trained very intensely during this game, like intelligence and technique under pressure. This applies to both the offensive players and the defenders in the middle. That is why Guardiola uses this drill almost every single practice.

A similar game that is used very often is called a Positional Game:

![A 4 vs. 4 + 3 Positional Game.]()

A 4 vs. 4 + 3 Positional Game.

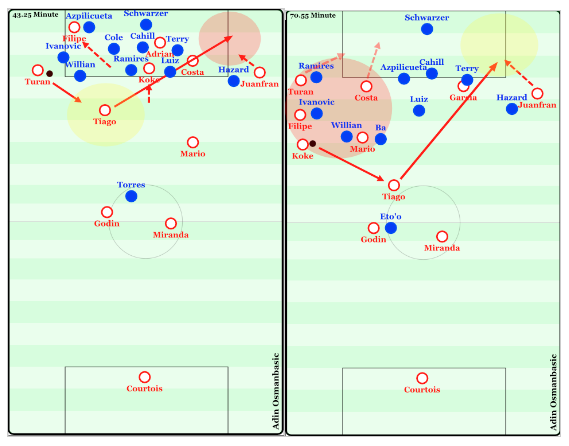

This game is played in a more rectangular area with the size of the area varying depending on the coach – similar to Rondos. The touches should be limited to 1 or 2 touches, though it is variable depending on the team and coach. In this game there are 3 neutral players (yellow) and a 4 vs. 4 possession game. The objective is to keep the ball as long as possible. Once the ball is lost, the two teams of 4 switch. There is a catch, though. When the ball is lost, the team that lost it can immediately counterpress.

This trains the ability and impulse to counterpress immediately when the ball is lost as well as the possessing team to immediately escape the area of pressure when the ball is lost. Along with similar fundamentals that are trained in Rondos, this game trains positioning in possession in between defenders, which adds complexity and pressure because there are 6 offensive players on the outside with 4 defenders in the center + 1 offensive player between them.

Some may argue that these games are missing actual goals to finish the play, but football is mostly progressing through zones with the movement of the ball and players in relation to the ball, rather than finishing on goal. In fact, if a team can progress through the field consistently well, they most likely won’t have finishing problems.

There are variations of these games that are possible with a “zone progressing” goal, meaning the goals of the drills are to keep the ball and manipulate the opponent while simultaneously progressing through various zones. These are very quick and high pressure games.

It goes back to the saying of Johan Cruyff where he said he wants players who can make the correct decisions in the smallest spaces. These games are used frequently in order to sharpen the players and teach them the most valuable aspects of football. During all of these drills Guardiola uses freezing of play and talking to his players to explain concepts and to coach the players. All of these aspects in training translate to the play of the team in real matches.

Game Analyses

Manchester City vs. Bayern Munich

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

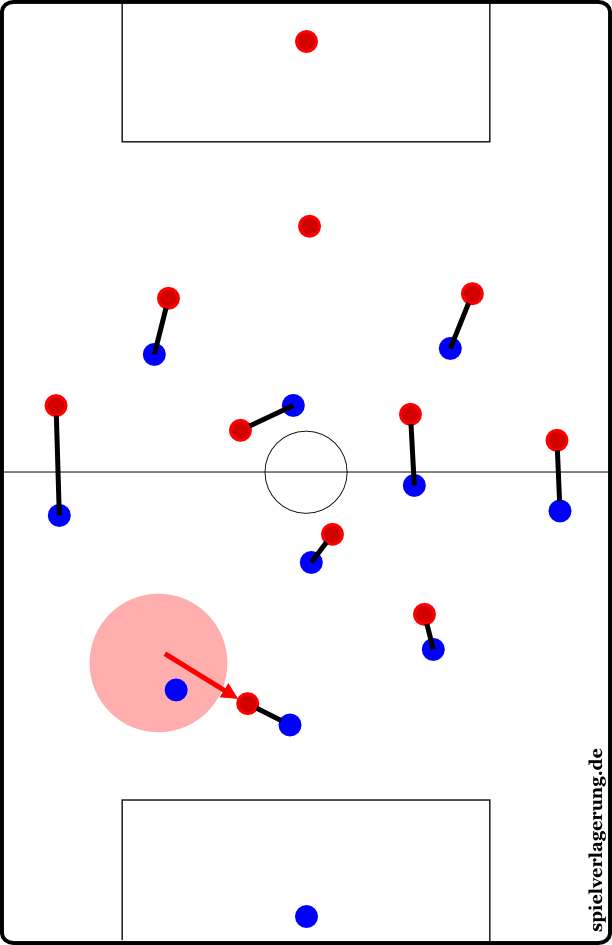

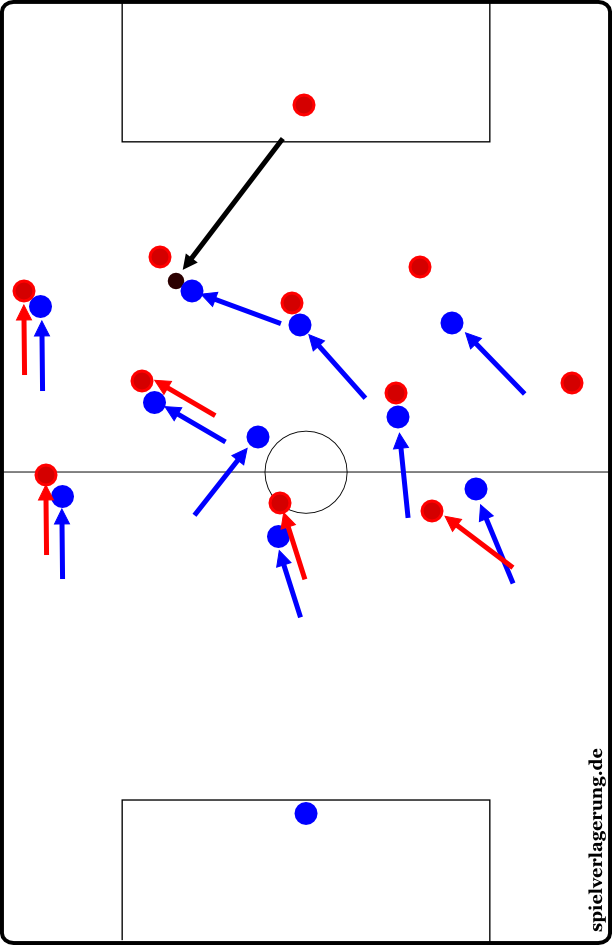

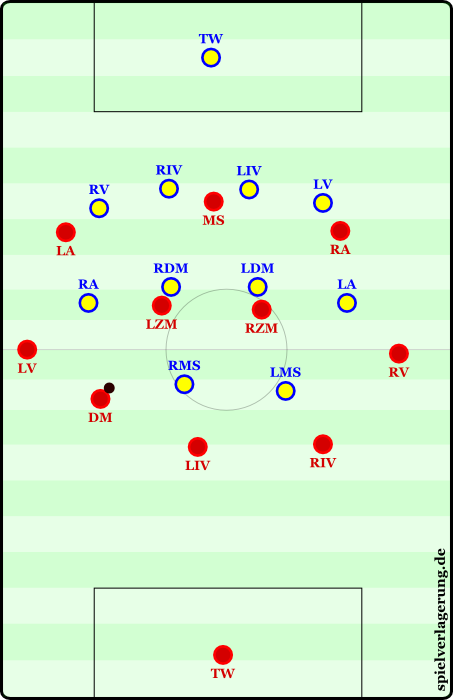

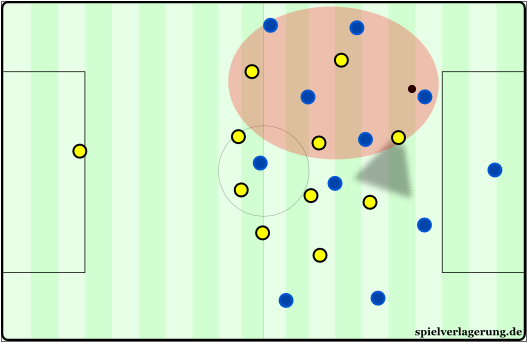

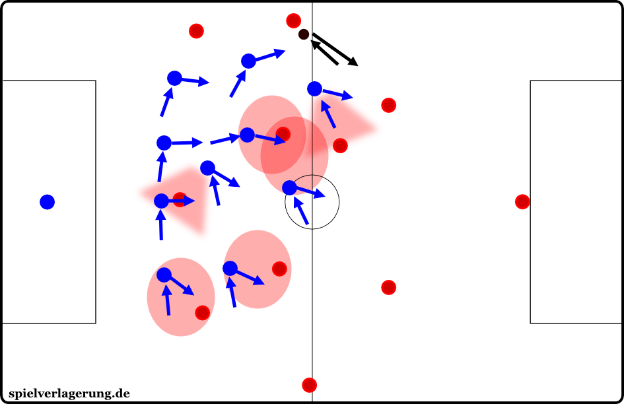

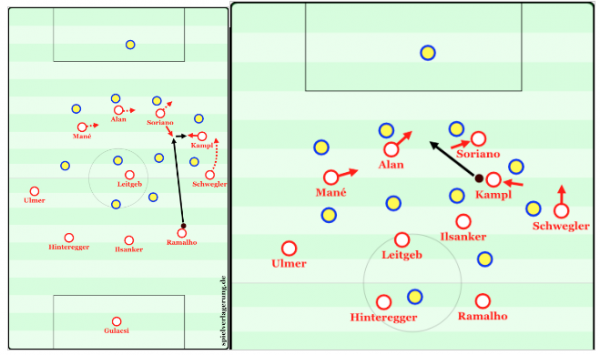

![Bayern's Positional Structure in Possession.]()

Bayern’s Positional Structure in Possession.

In this scene we see how Bayern support the man on the ball very aggressively. Including Neuer, there are 5 players supporting Benatia within the immediate area. On the far side the Bayern players make sure they are positioned so that they remain connected to the players in the immediate vicinity of the ball, even if they can’t support the ball themselves. This allows Bayern to play through the Manchester City pressure quite easily and progress up the field with ascending superiorities.

It also means that if Bayern want to finish the attack on the opposite side of the field in regards to the ball position, they are well structured to attack that area. Notice that the players all stagger and position themselves in a well oriented manner in adherence to the general rules of positional structure in the philosophy of Positional Play. This creates many triangles and diamonds which Bayern use to dominate the situation.

![Bayern utilizing the potential of the free man out of defense.]()

Bayern utilizing the potential of the free man out of defense.

Bayern use the 2 vs. 1 situation with Boateng and Benatia vs Aguero to their advantage in this scene. Here the back 4 are occupied by just Ribery and Lewandowski, meaning that Bayern already have a free man in midfield. To add onto this, Benatia invites pressure from Aguero and then Boateng receives the ball as the free man in the back line.

He proceeds to break through the first line of City’s defense and join the midfield. This creates a 7 vs. 5 overall match-up in midfield that Bayern can exploit and use to break through the opponent midfield. Also, notice that Alonso has dropped into the space on the left side of the 2 Bayern central defenders, in-between Bernat and Boateng.

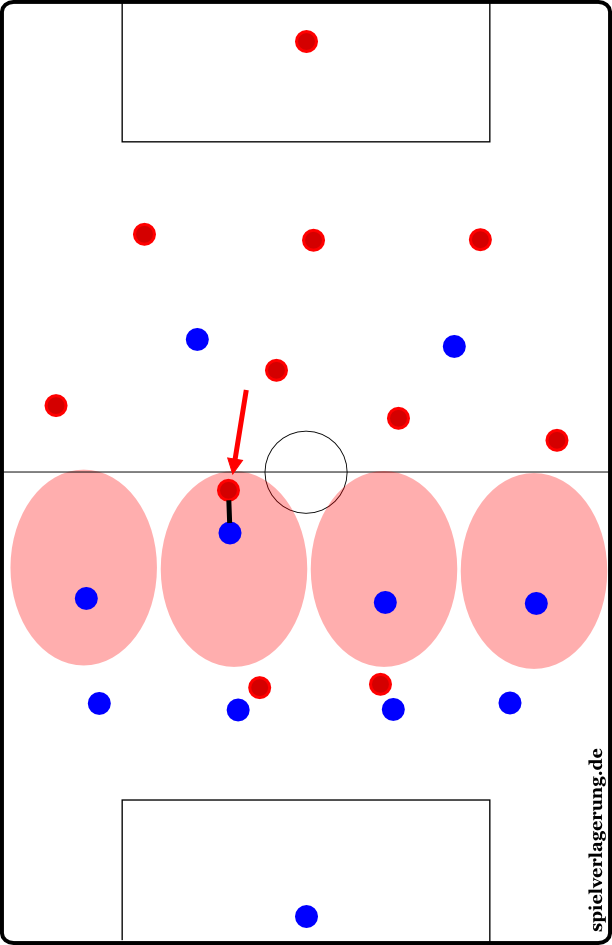

![Bayern manipulating Manchester City's defense even with 10 players.]()

Bayern manipulating Manchester City’s defense even with 10 players.

This scene takes place just before Bayern score their first goal after they have received a red card for Benatia’s tackle on Aguero. City was very easily manipulated by Bayern even though Bayern was down a man. This may be due to psychological factors in the game.

City realized they had an extra man, therefore they began pressing quite aggressively. Even though they pressed aggressively, City still occupied deeper zones with their defenders. This means that their pressure was not supported by further layers of pressing and they couldn’t gain any defensive access to the ball.

Bayern were still capable of using one player to eliminate 2 or 3 opponents in certain situations. In this scene there are roughly 5 players around Xabi Alonso while Hojbjerg positions himself excellently to maintain a passing lane between him and Alonso while still being positioned in the most dangerous hole in the City defense. The principles of moving the opponent with the ball and using the free man in the most dangerous areas still created a goal even against Manchester City with an extra man.

![Ribery drawing in many Manchester City players before releasing the ball into the opened space.]()

Ribery drawing in many Manchester City players before releasing the ball into the opened space.

This scene shows the buildup to the goahead goal Bayern scored with 10 players against a full City squad. Alonso passed the ball to Ribery in the center, who held the ball for a moment to invite extra City pressure before releasing the pass. The principle of starting the attack on one side and finishing on the other is apparent here. Also, Ribery managed to eliminate roughly 6(!) Manchester City midfielders with one pass.

This philosophy still shows its dominance in a Champions League match with 1 less player. While Ribery had adequate support near the ball, Boateng took up a position in the largest hole of the City defensive shape while maintaining connection to the ball. On a side note, Robben positioned himself very wide because he knew he was still connected to Boateng who could potentially receive the ball and potentially give him a pass. Once Boateng received the ball he played a long diagonal to the far post and Lewandowski headed in the goal.

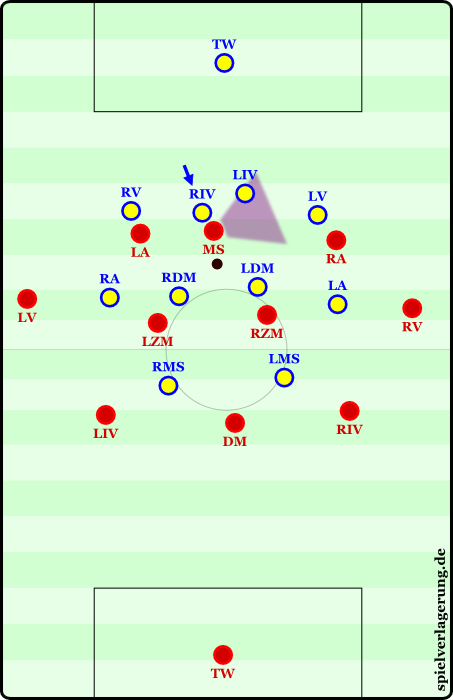

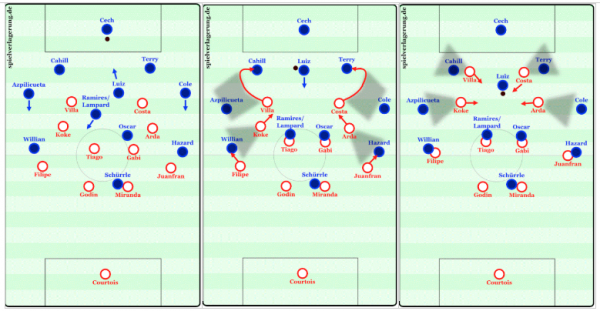

Bayern Munich vs. Borussia Dortmund

Saturday, November 1, 2014

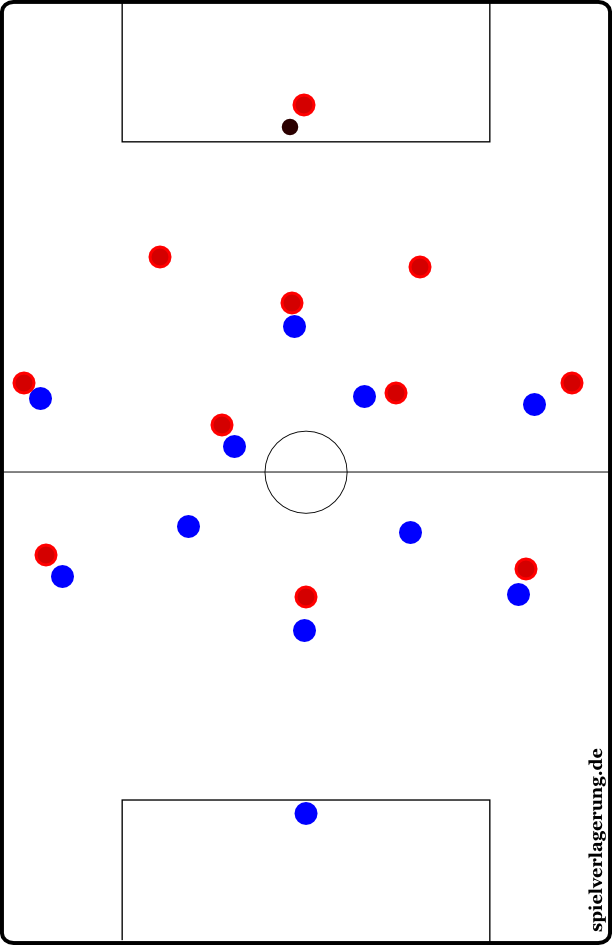

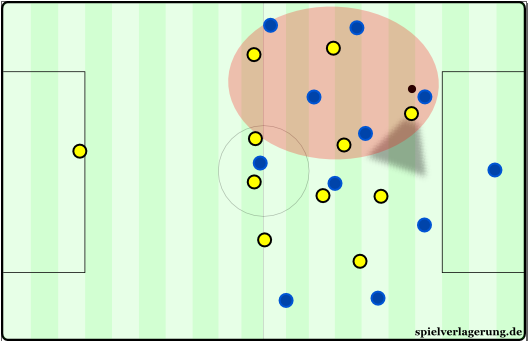

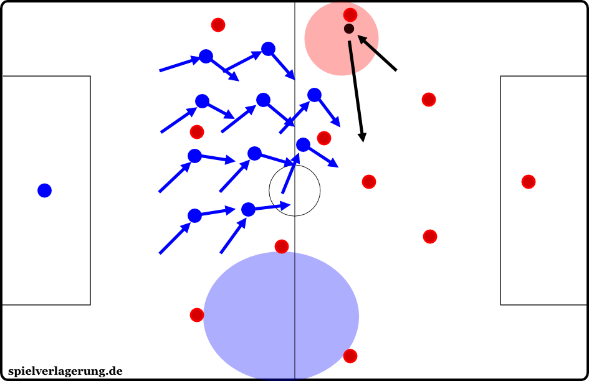

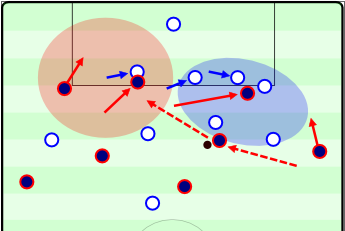

![Boateng playing one of his great laser-like passes through the lines of defense.]()

Boateng playing one of his great laser-like passes through the lines of defense.

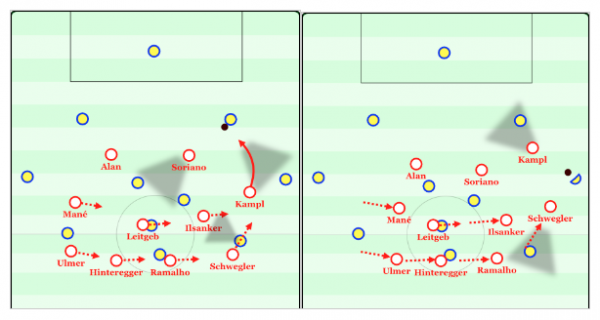

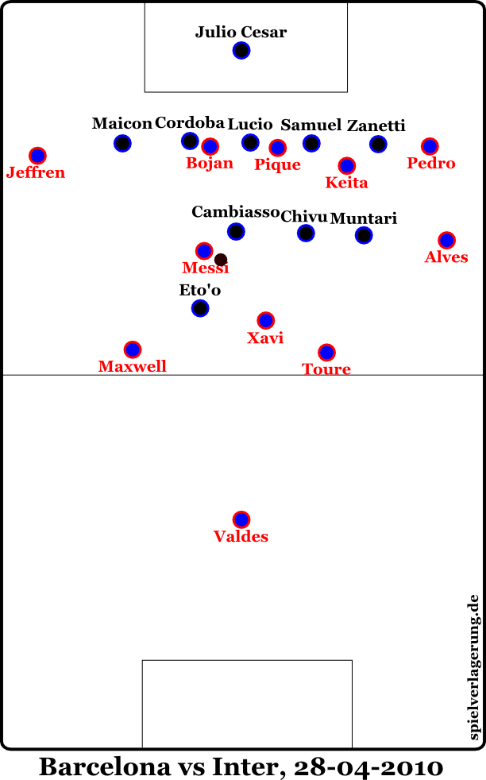

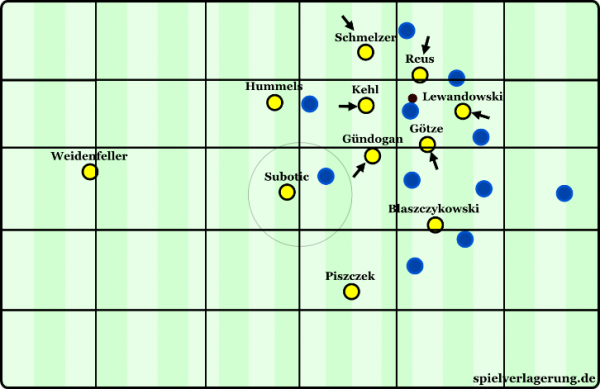

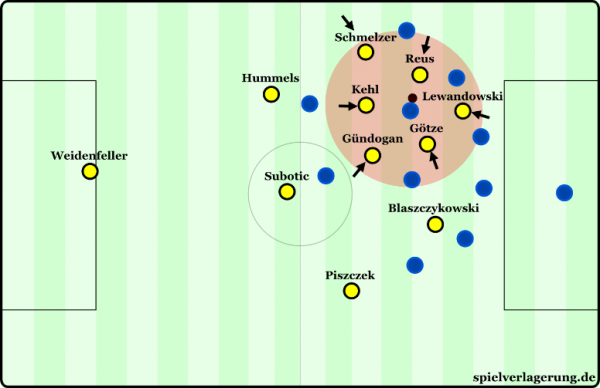

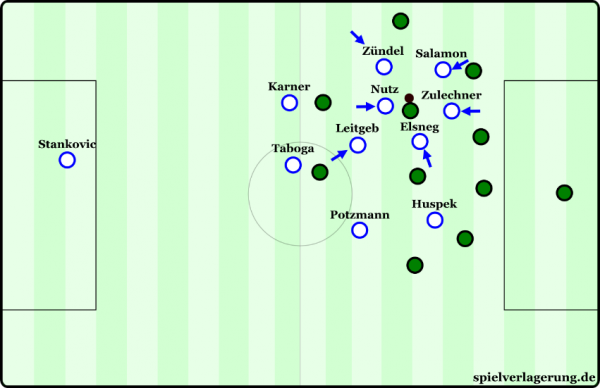

In this scene Boateng plays one of his impressive laser passes through the opponents midfield. Borussia Dortmund focused their entire defensive game plan on congesting the central areas of the field. This is because they knew this is what is most important for Pep Guardiola and his style of play.

Boateng received the ball from the left side of the field so when he turned to face the far side, there was a bit more space since the opponents have gathered on the near side. Boateng attacked the area farthest from Dortmund pressure and the scene ended in a dangerous Robben shot on goal.

The value of diagonal play can be observed here. Diagonal passes eliminate both vertical and horizontal lines of the opponent defensive shape. This eliminates a large portion of the opponent players while moving towards their goal and attacking through a zone that is usually underloaded by the opponent. Also, when attacking the field from one side diagonally towards the other the players have a connection towards varied zones, like the flank or the center. While attacking from the center means you have the same option on either side.

It also provides an optimal view of the field. If your players are attacking at a diagonal angle, that means their backs are facing the corners of the field which – are the least important. Also, depending on the position of the attack moving diagonally inside mean going towards the goal, while moving diagonally from directly in the center means slightly moving away from the goal.

In this scene Boateng was slightly offset towards the left and played a diagonal which 3 Dortmund players threatened but couldn’t reach. Once the ball broke through the pressure zone and reached Lahm, Bayern had an advantageous attack in central areas of the field.

![Neuer - not to be outdone by Boateng, plays one of his incredible penetrating passes.]()

Neuer – not to be outdone by Boateng, plays one of his incredible penetrating passes.

This scene exemplifies the value of Bayern Munich’s German goalkeeper. Manuel Neuer is considered by many the best goalkeeper in the world. Goalkeepers play a large part in the building game out of defense in this philosophy of play. Using the goalkeeper means you automatically have an extra pass option. It’s 10 vs. 11 because the opponent’s goalkeeper will not press high up the field due to the risk of leaving an open goal.

Using the goalkeeper in special ways in tandem with the defensive line is something we see frequently in Bayern. Here Neuer plays a long diagonal flat pass into the center while being pressured. The pass is incredibly accurate and Robben lays the pass off to Mueller who breaks through the Dortmund midfield in order to attack the defensive line. The effect of layoff passes are also visible in this scene. When a long pass is played, pressure gathers around the destination point. Once the pressure gathers and Robben plays a one-touch layoff pass to the forward facing free man, Mueller, Bayern have an extremely advantageous attack.

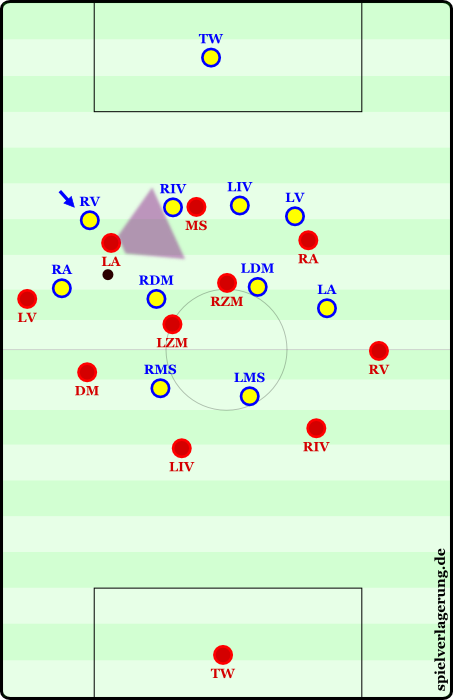

AS Roma vs. Bayern Munich

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

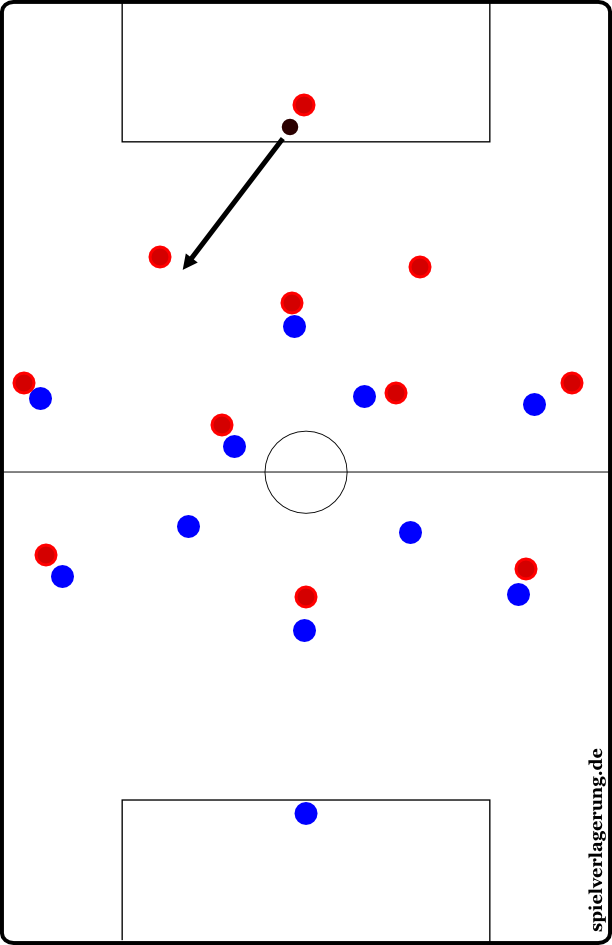

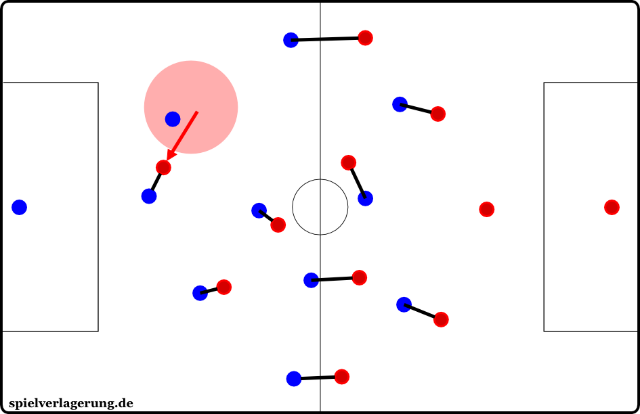

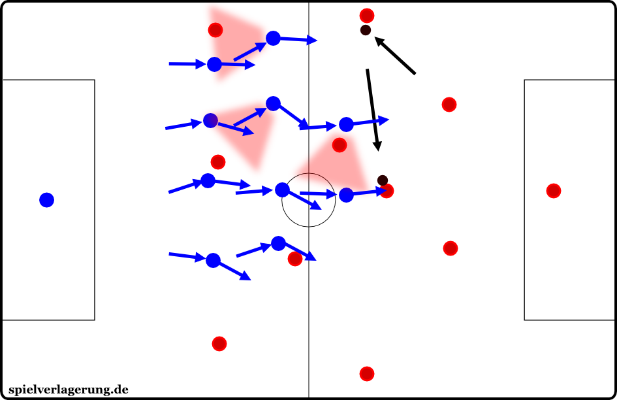

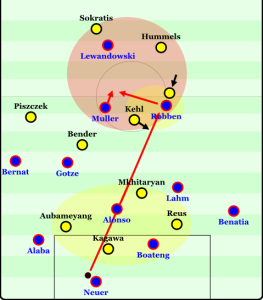

![Robben as the free man vs. AS Roma.]()

Robben as the free man vs. AS Roma.

This scene is from Bayern’s 7-1 victory over Roma. This shows the principle of the free man and his value to the attack. Bayern positioned their most dangerous player alone on the far side of the field as a free man. Robben is normally a winger so this position was perfect for him. Roma plays very compact horizontally which leaves the far side of the field open. Guardiola prepared for this match very well in terms of strategy.

Robben received the ball here and attacked directly towards goal, ending up in a 1 vs. 1 against Ashley Cole which is a very favorable qualitative superiority for Bayern. Note that once Robben goes diagonally inside to attack, Lahm immediately runs towards the flank in order to balance Robben’s movements and proved stability in the positional structure.

![Robben stretches the AS Roma midfield and allows for the ball to be played to Bayern's 3-man strikeforce easier.]()

Robben stretches the AS Roma midfield and allows for the ball to be played to Bayern’s 3-man strikeforce easier.

This scene is the buildup leading to Gotze’s goal and Bayern’s second goal on the night. Here the effects of Robben’s constant threat are visible. Since he was causing so many problems Roma began orienting their players more towards him. Robben was a constant threat that night and even scored 2 goals. Because of his output, the Roma defensive shape now lacked horizontal compactness.

That opened up vertical passing lanes into the trio of Gotze, Mueller, and Lewandowski through the stretched defensive connections of Roma. These 3 players are excellent in tight spaces and in combinations. This is another form of a qualitative superiority, only in a different manner. These 3 vs. the back line of Roma caused a goal in this scene. This was a great strategical game for Guardiola. His initial strategy opened up holes for the secondary strategy and Roma had no answers.

Bayern Munich vs. SC Paderborn

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

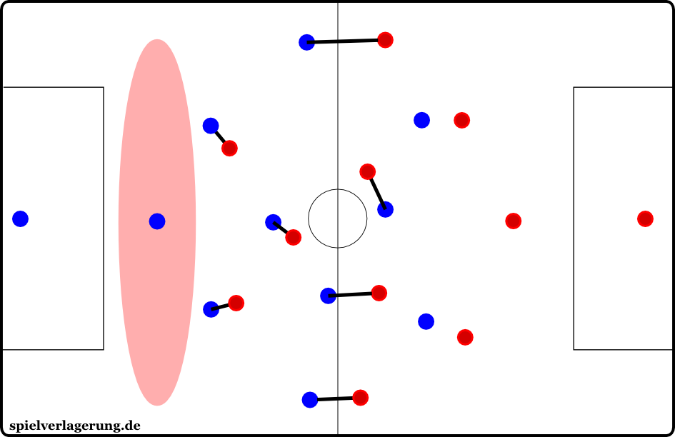

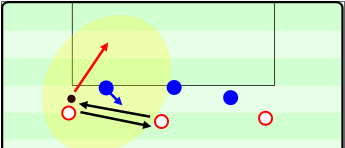

![Bayern overloading the right side.]()

Bayern overloading the right side.

Bayern varied their formation from the usual in this match. In this match they played a 4-2-3-1 formation with a specific strategy while still adhering to the principles of Positional Play. Bayern looked to focus on the interior corridors in this match and overload them to break through. Their numerical and positional superiority on the right side of the field is where the first goal stemmed from.

Here we can see the players still supporting each other in triangulations even when the play is very congested and tight on one side. This large amount of players around the ball meant Bayern had many players in good positions in case the was a ball loss and an opportunity for counterpressing. As you can see, Robben cut inside with the ball and Rode overlapped. In order to open space for Robben moving inside, Mueller moved to the flank as well.

Gotze and Lewandowski came close to the ball for a potential combination and break through while Lahm and Alonso provided safe back pass options. Rondos and Positional Play games have a strong resemblance to this scene specifically. This is an interesting example of a varied Bayern strategy and its relation to training.

Hertha Berlin vs. Bayern Munich

Saturday, November 29th, 2014

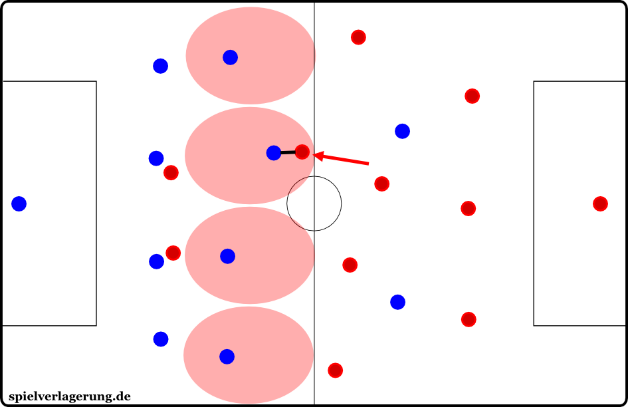

![Robben and Ribery in the interior corridors.]()

Robben and Ribery in the interior corridors.

“I look for [the opponent’s] point of weakness, and I try to put [skilled] players in those positions.”

– Pep Guardiola

This scene shows an interesting variation to the Bayern attack. In this game Ribery and Robben played mostly in the interior corridors instead of the flanks where we are used to seeing them. The idea behind this was that Hertha Berlin leave their central areas in midfield exposed because their wide midfielders man mark Bayern’s fullbacks. This means that Berlin’s formation is roughly a 6-2-1-1, which can be easily manipulated in the midfield.

Because the holes in the opponent formation are on the sides of the two central midfielders, in the interior corridors, Guardiola decided to let his 2 most dangerous players play in these zones. From here, Bayern attacked with Ribery and Robben diagonally towards goal with the positive effects of these movements mentioned in an earlier game analysis. Bayern’s goal in this match stemmed from such movement. The free men in between the lines are the most important players for Positional Play, and this match Bayern’s two best players were used in the most important positions in Guardiola’s Positional Play philosophy.

Conclusion

I would like to conclude by talking about the reason why Guardiola hates the term “Tiki Taka.” This term implies possession of the ball with no purpose, with no movements to disorganize and eliminate opponents. The idea of Tiki Taka is to keep possession for the sake of having possession.

Sometimes Guardiola will lose a game and people will say he plays this way, keeping the ball but not doing anything with it. Another reason he is accused of this sort of play is that many teams saw his style of play and tried to copy it without knowing the core principles, and in the end wind up with nothing but pointless possession.

The Spanish National Team that made history from 2008-2012 had times where they played this way, and the players in that team were Guardiola’s players. Maybe similar accusations will arise if Germany start playing poorly now that he coaches Bayern Munich, though they just won the 2014 World Cup with a style of play similar to his Bayern Munich team. In the end, these are not his teams, but other teams that may give this idea of possessing the ball a bad name.

So yes, possession of the ball psychologically frustrates the opponents because they cannot do what they want to do. Continuity and flow of possession for a long duration does bring a sense of control. But possession is merely a consequence of the offensive game of Pep Guardiola and his principles.

Possession is not the goal, though the possession of the ball provides the innate defensive aspect that one team has the ball and the opponents cannot score because they don’t. Scoring goals, defending, and keeping possession are consequences of this philosophy of play, not the focus. The focus is to play good football and to win by doing so. Pep Guardiola wants to win in any way possible, but he believes this is the very best way to win.

Footnotes

[1]: Maurizio Viscidi is well known in Italy as one of Arrigo Sacchi’s best students and assistants. He is also a well known “Giochi Di Posizione” coach. Maurizio has worked as Director of Youth Development, Technical Coach, and Assistant Coach under Cesare Prandelli and Antonio Conte for the Italian National Football Team.

[2]: Marti Perarnau is a former Olympic Athlete who is the author of the very popular “Pep Confidential” book where he spent an entire year with Guardiola during his first season at Bayern Munich. He is also the author of Perarnau Magazine.

[3]: Juan Manuel Lillo is a pioneer of Juego de Posición. Pep Guardiola has said many times he goes to Lillo for advice. Lillo coached Guardiola as a player in his 2005-2006 season as a manager at the Mexican club Dorados de Sinaloa.

[4]: Ricardo La Volpe is a famous Argentinean coach. He won the 2003 CONCACAF Gold Cup with Mexico. Pep Guardiola notably fell in love with his 2006 Mexican National Team. The Mexican National Team lost to Argentina in the Round of 16 2-1 after extra time in that World Cup. These results brought Mexico to 4th in the FIFA World Rankings.

[5]: Paco Seirul-Lo is a fitness coach in FC Barcelona. He was the Head of Fitness Coaches under Johan Cruyff when he was appointed in 1993. He is a Spanish Sports Scientist who studied Kinesiology at the Instituto Nacional de Educacion Fisica in Madrid.

[6]: Arrigo Sacchi coached AC Milan from 1987-1991 and 1996-1997. He won two European Cups back to back in 1989 and 1990. Sacchi is famous for his contribution to the Zonal Marking style of defense.

[7]: Johan Cruyff is arguably one of the best players and coaches in the history of the game. He won 3 Balon d’Ors. He was coached by the father of “Total Football,” Rinus Michels. Pep Guardiola considers Cruyff his largest influence, being coached by him and winning 4 La Liga’s from 1991 to 1994.

[8]: Oscar Moreno is the author of “Modelo de Juego del FC Barcelona.” He is currently a coach of CD Alcoyano.

[9]: Siegbert Tarrasch was a German master of chess. He had many books on chess and contributed many things to the game of chess.

[10]: Frank Rijkaard was a great central defender and defensive midfielder for Ajax and AC Milan, playing for coaches like Cruyff, van Gaal, and Sacchi. He was also the manager of FC Barcelona from 2003-2008, winning the Champions League in 2006.

[11]: Angel Iturriaga Barco is a Spanish writer and historian. He is the author of various dictionaries about FC Barcelona and about Spanish Football.

[12]: Interior Corridors are also known in German as the word Halbraum, literally translated as Halfspaces. My colleague Rene Maric created a tactical theory piece on the importance of this zone here.

Acknowledgements

Special Thanks To:

Marti Perarnau

Rene Maric

Daniel Trejo

Felipe Araya